Publications

25.07.2022

20 min read

Analytics

Diaspora and Economic Development: A Systemic View

-webp(85)-o(png).webp?token=192bf9d1bebd20d94178008b69bda875)

Abstract

Recent attempts to generalize isolated successes of expatriate entrepreneurial networks offer limited insight into the more systemic questions on the role of diasporas in sustainable development of small economies. Drawing on experience of post-socialist transition and merging multidisciplinary perspectives, this paper advances a constructive critique to the conventional views. A historically multilayered socioeconomic construct, diaspora is in fact heterogeneous, often, lacking a unified stance and as such likely diminishing the relevance of the simplified first-mover business case study effect in development. Informed by an original survey, this paper proposes a new diaspora driven development framework of analysis. Any successful engagement of a diaspora with its homeland is a function of sustained interaction between the two entities. In the absence of transparent engagement infrastructure, diaspora’s links with a developing economy are short-lived and, usually, sector, event, or location specific. This analysis adds to the literature on the common good dimension in development where individual well-being is a systemic component of a larger outcome rather than the final aim.

Introduction

The macroeconomic patterns evolving since the early 1990s in the small post-socialist economies of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and the former Soviet Union (FSU) are yet to lead to a path of sustainable economic development (e.g., Gevorkyan 2018; Roaf et al. 2014). Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has unveiled dormant structural flaws risking “lost decade” in development (UNCTAD 2020), prompting a search for non-conventional sources of economic recovery. With these concerns, the role of national diasporas in the region has resurfaced. Maintaining a broad perspective, this paper attempts to systemically review diaspora’s significance in economic development. This paper’s approach stands in contrast to the literature’s focus on isolated industry or localized successes. In its effort, the paper echoes and is motivated by the earlier work on distinction drawn by Deneulin (2006) between common good and individual human well-being in economic development. The dichotomy of the modern development is such that incentives that help maximize well-being outcomes of individual migrant households, forming the diaspora, do not necessarily equally contribute to a more macro-outcome of the home country’s development progress, the common good.

The literature on the promise of national diasporas, as potential conduits for economic development and institutional change in their ancestral homelands, the so-called first movers, spans across academic traditions and country cases (e.g., Newland and Patrick 2004; Larner 2007; Riddle and Brinkerhoff 2011; Clemens et al. 2015). Recently, Panibratov and Rysakova (2020) constructed a comprehensive catalogue of key thematic clusters of the business literature on diaspora. The authors identified five main research directions based on their analysis of over 400 papers published on the concept of diaspora. The first cluster identifies literature exploring the many aspects of the home and host countries’ development, often localized as specific country case study. The second research cluster deals with the role of the diasporas in fostering international entrepreneurial activities. The third cluster pools vast literature on diaspora from China’s perspective, with an emphasis on returnee entrepreneurship. Finally, both the fourth and fifth clusters focus more on topics of international marketing (e.g., tourism management and cultural identity).

The present paper connects with the first cluster in an effort to inform home country’s diaspora policy and advancing a systemic model of diaspora for development. In national policy, as Kunz (2012) emphasizes (following, Larner 2007), the discovery of diaspora by the home country is neither new nor unique. Attention to the diasporas brings with itself a complex combination of economic and political aspects of new agent participation, accounting for the heterogenous nature of the diaspora. This complex political economy argument, is often omitted in the work based on business case studies, prioritizing the individuality of achievement with an implied expectation for replication on a broader economic scale. The present study bridges the parallel themes connecting with the complexity and perception of the diaspora concept.

The conventional view is that diasporas benefit from new technology, mobility, and self-preserving network effects. The potential for a collective skills transfer by diaspora professionals to the ancestral home can spur growth across diverse industries, as is often mentioned with regard to India’s information technology (IT) sector (Pande 2014). Yet, in the absence of accurate data on the diaspora potential and lacking a clear infrastructure in place to realize such a fruitful engagement, much of the debate tilts toward what can be called “diasporization” in economic development. External agents of progress (entrepreneurial and skilled members of the diaspora as well as diasporic organizations) are often generalized as having a broad positive (potential) impact on the basis of isolated examples. In reality the contributions of the diaspora to development are often ad hoc, or, at best, dispersed compared to the scale of the home country’s economic needs (e.g., Tölölyan 1996, 2007). To date, despite many attempts, no general sustained institutional engagement infrastructure has emerged to take advantage of the diaspora potential, leaving it much discussed but largely untapped (Aguinas and Newland 2011).

Exploring these arguments with additional detail and building on results of a unique Armenian Diaspora Online Survey (ADOS), this paper explores opportunities for diaspora’s systemic contribution to small home country’s sustainable economic development. Connecting the discussion with the CEE/FSU helps to isolate some common pitfalls and possible opportunities that may be relevant elsewhere in the developing countries. This paper attempts to address three questions in such context. Is existence of a diaspora (or discovery of such) sufficient to ensure a common good positive contribution to macroeconomic development filling all structural voids? What is the true diaspora potential? Finally, what infrastructure can be adopted to ensure the optimal outcome?

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Moving away from the comfort of the “diasporization” view, “Conceptualizing the Types of Diasporas: A Dispersion” section strikes at the unified diaspora perception by introducing the distinction between the “old” and “new” age diasporas in a dispersion. “Measuring the Effectiveness of Diasporas” section addresses the effectiveness of the current diaspora’s economic impact. “Some New and Not So New Policy Proposals” section reviews some of the possible policies that could optimize diaspora engagement. “The Armenian Diaspora Online Survey” section presents the ADOS and briefly describes the diaspora portal concept as contributing to diaspora engagement infrastructure. “Self-critique and a Diaspora Model of Development” section develops a more systemic model of diaspora for development in small economies. The paper ends with a summary of conclusions.

Conceptualizing the Types of Diasporas: A Dispersion

Diaspora networks, which often formed because of historical or recent economic, social, and political turbulence, have long since been popularized as conduits of economic development, helping to combat poverty, promoting job creation, and transferring technology, knowledge, and best business practices to their country of origin. But the connection is not immediate. In business and economic literature, substantial population loss is seen as furthering a brain drain. A strong diaspora in a rich (or politically stable) economy raises probability of emigration from a relatively weaker economy. Bang and Mitra (2011) point to a positive effect of a country’s higher quality of institutional capacity (e.g., specialized education) on greater incentives to emigrate for higher-skilled workers than for lower-skilled ones, even in the presence of political stability. Over the longer-term such high-skilled emigration may lead to possible positive feedback to the home country by way of knowledge diffusion (some examples are mentioned below).

Spanning across clusters identified in Panibratov and Rysakova (2020) the recent literature on development has placed high hopes on the diaspora investors and positive results from a larger return migration (e.g., McGregor 2014; Boly et al. 2014; Ketkar and Ratha 2010; Freinkman 2001). Yet, the practical difficulty of having diaspora entrepreneurs and professionals as the first movers into the developing economy (i.e., preceding any possible investments from multinational corporations) requires a clear understanding of the nature of the relationship between the home country and its diaspora. In this respect, attention to the expatriate groups formed by recent migration waves alone does not seem to be telling the full story.

One factor that has gone largely unnoticed is the diaspora age. This is not in relation to individual diaspora members’ age. Instead, the focus is on a collective characterization of the diaspora group that someone in the diaspora associates with based on a range of objective factors leading to the community’s formation. Historically, the waves of outward migration from CEE and the FSU (and within) have contributed to burgeoning diaspora networks shaping altruistic motives by the “old” groups. Within each community one might identify several such migration waves, depending on the time frame. The “old” diaspora is comprised of citizens of the host countries to which either they or their ancestors emigrated long ago. The “old” group retains nostalgic impulses to assist distant countries of origin. The “new” diaspora is largely made of immigrants following the post-1990s independence and more recent labor migrants.

Conceptually, the “old” diaspora has common ethnic or religious roots with the “new” diaspora, and the members of this “old” diaspora have cultural (and some tangible) ties to their ancestral homeland (which may not be their birth country). By definition, the “old” diaspora is a more established and, often, more affluent entity. Migration of the “new” sustains the “old” diaspora clusters, potentially motivating strong interest in the development efforts in the ancestral home through humanitarian aid or other “soft” (e.g., educational, cultural exchanges) projects. Because, generally, it has greater institutional business leverage, the “old” diaspora’s relationship with its country of historical origin (home country) can lead to significant positive development feedbacks, depending on the effectiveness and strength of the link between the two entities.

While precise estimates of diaspora communities are rare, much of the evidence comes from host country censuses and home’s dedicated diaspora agencies. In the FSU, the size of the “old” diaspora, formed in the second half of the twentieth century, is consistently large due to regular population movements through the twentieth century (e.g., see Gevorkyan 2018, Table 8.4; Heleniak 2011, 2013). Here, host economies and communities with established “old” diasporas tend to attract “new” migrants. The determining factors may be the prospect of economic opportunity or geographic proximity to the country of origin (Gevorkyan and Gevorkyan 2012).

The distinction between the “old” and the “new” diasporas is critical for understanding the success or failure of diaspora-driven development and assessing the diaspora potential. Such approach helps to avoid a definitional problem implied by the often-assumed conceptual uniformity of the diaspora. There is a significant degree of over-layering between the “old” and the “new” diasporas within developing countries. For example, in the Caribbean, large numbers of Guyanese live in Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, and elsewhere. Following the emancipation in 1838, Caribbean nationals were brought to British Guiana before subsequent migrations from India, China, and Portugal adding to the mosaic of the Caribbean diaspora these days (Khemraj 2015).

Therefore, treating as monolithic any ethnic, cultural, religious, or other kind of diaspora to be a priori altruistically (or otherwise) interested in development of their country of origin is bound to lead to disappointment. The result is the fallacy of diasporization in the expectation of an almost guaranteed positive diasporic development effect.

Rather, the term dispersion—as in a widely scattered distribution of people, resources, ideas, and actions—more accurately characterizes the complex web of factional, political, business, and other divisions, interwoven with the history of an expatriate community that has some type of common background (e.g., on contemporary diaspora definitions and the applications in interdisciplinary studies in Tölölyan [2007] and on diaspora policies in Larner [2007] and Kunz [2012]). Here, the inherent diversity of experiences, the dispersion effect, can act as a brake on the development of the home economy, instead of helping to drive it. The dispersion concept underscores the heterogeneity in a wide range of diaspora backgrounds. Although the representatives of the “old” and the “new” diasporas [and, in fact, within each group itself] may share some views of their home country on major strategic matters, their practical actions, ideas, and beliefs on other country and community specific topics can be, and often are, in conflict (Gevorkyan 2015).

Added are even greater divisions between the expatriate community and the home nations. The dispersion effect is exemplified in varied efforts at involvement and yet lack of systematic institutional engagement aimed at comprehensive development, aside from a multitude short-term humanitarian and cultural projects. For a detailed narrative on the different modalities in relations between diasporas and their countries of origin in CEE/FSU, see Heleniak (2011, 2013). This brings us to an analytical assessment of the effectiveness of diaspora networks in development and poverty alleviation specifically. We connect the discussion with a more recent phenomenon of large-scale labor migration.

Measuring the Effectiveness of Diasporas

There are at least two normative statements one can make about temporary labor migration in the diaspora for development context. First, there is nothing more permanent as temporary migration, as the CEE/FSU experience broadly suggests. Second, temporary labor migration can make a (temporary) positive contribution to poverty reduction through the transfer of regular remittances and skills (e.g., Aguinas and Newland 2011; Newland 2010; Ratha and Mohapatra 2011). Yet, if left to its own devices, the ad hoc temporary labor migration model does not lead to a sustainable development in the small economies.

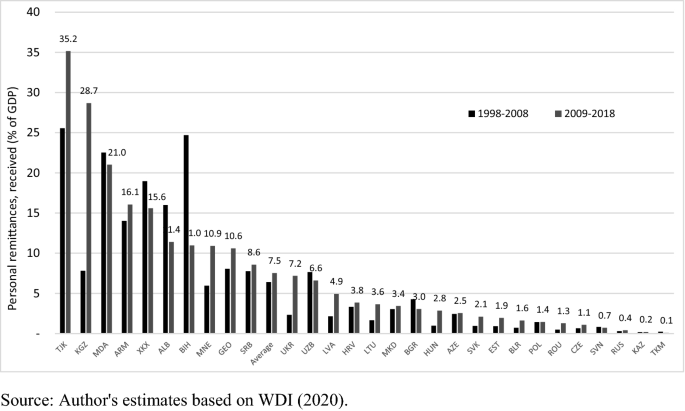

The typical labor migration cycle follows rounds of short trips. As breadwinners often eventually emigrate with their families, the home economy is effectively cut off from remittances financing. At that stage temporary migration becomes permanent. Still, the role of regular financial transfers (remittances) in some CEE/FSU economies has been quite important (Fig. 1) in alleviating immediate poverty pressures, helping individual households to fund medical, educational expenses, and, often, contributing to local consumer markets. Reflecting on the heterogeneity of diasporas and migration, distribution of remittances by recipient country is not balanced. Remittances remain to be the major source of household consumption budget in a few small economies, while being of a lesser significance in others.

Fig. 1

Personal remittances received as a share of GDP in the CEE/FSU (%)

On the global scale as of mid 2020, remittances were expected to drop by 20% compared to the previous year with a disproportionate detrimental impact on the least-developed economies (World Bank 2020). From a macroeconomic perspective, it may be argued that reliance on remittances can erode the competitiveness of the domestic labor market. Steady unconditional financial inflows boosting consumers’ higher purchasing power may easily outweigh the incentives to compete for jobs in the local economies (e.g., Chami et al. 2008). Furthermore, Chami et al. (2018) argue that evidence of remittances’ contribution to small economies’ growth is lacking. Elsewhere, Nissanke (2019), in a recent analysis of structural transformations of small economies in sub-Saharan Africa, argues that diasporas are active participants in development finance. The premise is that diaspora’s first movers are ready take currency or other country risks leading the global investors to the home economy. A steady inflow of remittances may be seen as potentially ushering such tidal change in development finance.

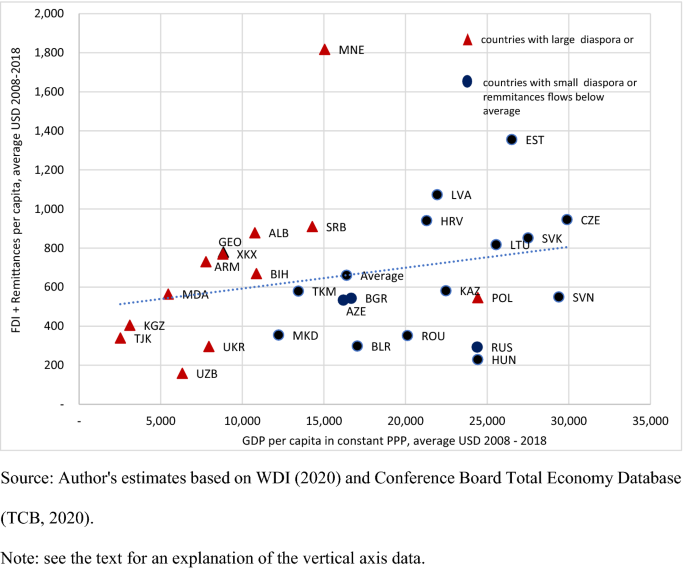

As a high-level take, we construct a diaspora dependent indicator for external financial inflows in a cross-country comparison for CEE/FSU. Figure 2 compares the country’s sum of foreign direct investment (FDI) and remittance inflows per capita to the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita between 2000 and 2018. The results in Fig. 2 show some countries with relatively modest post-transition recovery in GDP per capita but with high inflows of combined external investments (e.g., Croatia, Hungary, and combined Serbia and Montenegro). There are also those with strong per capita income growth but relatively weak external inflows. For the top performers, FDI flows play a much greater role than remittances. To some extent, this observation is also consistent with the fact that countries with smaller income gains (bottom left from the average point) have smaller per capita inflows.

Fig. 2

FDI and Remittances per capita vs. GDP per capita, 2000–2018 (USD)

On balance, however, the evidence is mixed. Countries with high diaspora potential seem to be underperforming on the FDI-remittances per capita measure. It appears that those countries have not attracted significant levels of external investment in per capita terms, which raises two concerns.

First, the large-diaspora country’s attractiveness for capital flows is not a given. Becoming involved in global capitalism also means entering global competition for limited financial capital, which is a challenge for emerging markets. Having a large diaspora does not seem to guarantee strong results. Second, the collective “old” and “new” diasporas potential appears to have not been fully sustainably mobilized. The inability to secure sustained external financing either to motivate domestic aggregate demand or longer-term investment projects (via FDI) is a serious deterrent to macroeconomic development models in some of the post-socialist small economies. Elsewhere, another challenge to diaspora might be less where to invest or how to allocate resources in formal terms than the inability to penetrate local markets. Over the three decades since the transition reforms, the evolving local business networks are now competing with potential diaspora capital. For the domestic firms, financial and project-driven investment by expatriates is competition, rather than a national development support. Such dialectical dynamic between the local and diaspora businesses requires a more careful dedicated analysis.

As found in Fig. 1, only a handful of the CEE/FSU countries benefit from high (and consistent) remittance inflows. Furthermore, recent World Bank data (WB 2020) corroborates the dominance of a single source of remittance revenue in most cases (primarily, monetary transfers are initiated by the “new” diaspora, mainly, labor migrants from either Russia for the FSU countries or EU/UK for the CEE). That raises concern about recipient countries’ sustainability and susceptibility to business cycles in senders’ countries.

There is also a question of the spending direction of remittances. Piras et al. (2018), focusing on agricultural changes in Moldova, find that remittances from labor migrants received by rural households gave them only limited flexibility in decisions about farm-related upgrades. Moldova is one of the highest recipients of remittances from labor migrants, as they contribute over 25% of GDP. Most of those transfers seem to fuel consumer markets, rather than going toward productive use, as agriculture is dominated by conglomerates, and small farms lack access to a broader inclusive finance scheme.

In a study on the Philippines, which has one of the most developed systems of labor migration and remittance flows, Licuanan et al. (2015) find that the diaspora’s (read, labor migrants’) financial contributions to the home country rise with migrants’ income earned abroad and the frequency of hate crimes against migrants in the host countries. Some evidence also indicates that money flows to recipient countries with higher emigration, rather than those that are the least developed.

What we learn from these observations is that, from a broad macroeconomic development perspective, diaspora-led financial transfers tend to be altruistic, humanitarian, supporting a specific project but largely aimed at individual household support. This is also consistent with the analysis of the management and business literature on diaspora in Panibratov and Rysakova (2020). Despite their statistical significance for domestic financial flows and consumption expenditure, there is limited evidence that individually motivated, short-term, monetary transfers lead to sustained structural transformation in industrially weaker economies.

As such, there is no lack of initiatives exploring the “beyond remittances” (e.g., Newland and Patrick 2004) multiplier effects from diaspora-led FDI, technology transfers, philanthropy, tourism, political contributions, and cultural influences. Despite limited scale and available data, some evidence suggests that in economies with wide diaspora networks, the “old” diaspora’s active business role has been critical to some macroeconomic gains (e.g., Armenia, Georgia, Poland, and Ukraine). In Armenia, for instance, diaspora business networks are the source of over 60% of recent FDI and multinational enterprises either started by or with influential management representation by diaspora professionals (e.g., GIZ 2011). Yet, Armenia does not score highly on the Fig. 2 composite FDI and remittances index.

For Georgia and Moldova, large-scale migration began with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, whereas Armenia’s Western diaspora has been in existence since at least the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (see Aslanian 2014 on even earlier Armenian diaspora merchant networks). In contrast to the Armenian diaspora, the Georgian and Moldovan diasporas are relatively small, new, and have not demonstrated the same level of broader economic vibrancy in home-host country engagement (GIZ 2012).

But what type of diaspora-to-home country involvement is adequate for guaranteeing a strong and lasting contribution to the domestic economy in general or any specific sector? A handful of countries (e.g., Armenia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Moldova, Poland, Tajikistan, and Ukraine) have tried to put some of these mechanisms in place (e.g., Gevorkyan 2018; Heleniak 2011; Newland 2010). For example, Armenia and Georgia now have ongoing initiatives in education, humanitarian, philanthropic, and political areas involving individuals from the “old” and the “new” diasporas. Both have adopted a dual citizenship law (joined by Moldova and the Kyrgyz Republic).

Across the region, the practice of “fuzzy citizenship” has evolved, which means a status that grants semi-permanent residence to the diaspora (Skrentny et al. 2007). For example, Poland has established a “card of the Pole” allowing a member of the Polish diaspora to obtain a work permit, establish a business in Poland, gain access to the country’s education system at no charge, and attain other benefits normally unavailable to citizens of other countries (MFA 2015). Other countries either initiate (as in the Polish model) or create the conditions for expatriate entities to engage (e.g., BirthRight and RepatArmenia groups in Armenia) in economic and social activities (for a thorough review of the involvement of each diaspora in its country of origin, see Heleniak [2011]). Elsewhere, some of the smallest economies across the CEE/FSU have launched targeted efforts attracting diaspora’s entrepreneurial capital towards niche technological sectors in the country (e.g., Unity Through Knowledge Fund in Croatia; Georgia’s Innovation & Technology Agency in the Republic of Georgia). In Moldova, a recent Migration and Local Development project implemented by the UNDP has helped channel diaspora’s human and financial resources towards the rural communities’ development.

A Midway Assessment

The cumulative evidence so far points to two thoughts. On the one hand, although some social and macroeconomic improvement is undoubtedly due to diaspora actions, the dispersion effect of the scattered, unorganized nature of those efforts might be a net negative disincentivizing and slowing homegrown competitive economic progress. On the other hand, if a country’s fundamental macroeconomic and political environment is relatively predictable (e.g., as in some CEE countries that are European Union member states), dispersion is likely to have a more positive effect. In that case the economy benefits from having a variety of medium- to long-term investment and cultural projects, driven in part by diaspora organizations, often transforming domestic institutional arrangements (the latter point raised by Riddle and Brinkerhoff 2011).

Broadly, the variations observed in the diaspora engagement models can be explained by (1) the geographic distance between the expatriate’s current country of residence and country of origin; (2) the relative significance of the “old” and the “new” diasporas’ motivations; (3) political stability and macroeconomic conditions in the country of origin; (4) the expatriate’s legal status in the host country; and (5) the existence of a functional engagement infrastructure for the diaspora’s involvement in the home economy.

Recent evidence suggests that almost every CEE/FSU country has formally acknowledged some type of relationship with its diaspora through humanitarian projects or diaspora participation in the country’s public life (Heleniak 2011). Yet, on the practical side there is still the lack of systemic, large-scale institutionalized involvement of the diaspora in macroeconomic development of its country of origin. It is at this juncture that the realization of the failure at achieving a common good (as defined by Deneulin 2006) in economic development, despite individual successes at a level of a migrant family, small community, or even isolated industry, becomes a policy challenge.

Some New and Not So New Policy Proposals

There is a range of policy proposals that have been tried and discussed in fostering an effective diaspora for home country development model. Connecting with the discussion in the previous section, most of the proposals focus on streamlining financial flows towards the home country. The diaspora bond proposal, a topic well covered in Chander (2001), Gevorkyan (2011), and Ratha and Mohapatra (2011), is one of such initiatives. Though it is doubtful that labor migrant remittances may be the primary source for a diaspora bond, conceptual discussion revolves around patriotic discount. Altruistic diasporas are hypothesized to accept lower competitive returns on investment, and greater currency risk tolerance as diaspora members invest in instruments denominated in the local currency (e.g., diaspora bond issuers in sub-Saharan Africa, Nissanke [2019]). In that regard, as new technology emerges and financial markets deepen across developing countries, new modes for diaspora investors’ participation in the home economy may appear.

Alternatively, diaspora micro-loans to rural areas and diaspora business-funded basic income programs are other methods of proactive financial involvement beyond just migrant remittances. Such programs may help connecting the efforts of “old” and “new” diasporas. The diaspora micro-loans can be advantageous in particular for post-socialist economies with limited exposure to global capital markets, limited FDI inflows, and a still-evolving banking system.

Elsewhere, Gevorkyan and Gevorkyan (2012) introduce a diaspora regulatory mechanism (DRM) coordinating temporary labor migration’s remittances flows to a migration development bank (MDB). The DRM engages the “old” diaspora, which integrates and even employs the “new” labor migrants. In this framework, the MDB helps smooth any abrupt disruptions of the remittances flows to the home economy. Operational transparency could be gained by involving members of both the “old” and the “new” diaspora in a Diaspora Supervisory Board as a policy-setting and decision-making entity.

As a bilateral bank (between host and home economies), relying on newest financial technology and mobile banking, the MDB could offer a systemic alternative to the currently ad hoc remittances, channeling them into savings accounts that are accessible to home-country recipients. The bank can then raise funds for and sponsor development projects in the home’s infrastructure, education, and health care as well as tackle poverty and environmental and sustainability issues, tackling these migration-push factors directly. The MDB would attract new diaspora investors who are hesitant about entering the market in their country of origin. For a non-diaspora investor, who is unfamiliar with local conditions but seeks portfolio diversification, an MDB sponsored fund could be an alternative that would facilitate initial entry to the local market. The host economies would benefit, as some of the funding could be directed to better administration and regulation of labor migrants in their home countries (e.g., financing diaspora centers, publications for labor migrants, and efficient fast-track immigration screening).

Globally, there are non-systemic prototypes for MDB-type scenarios (e.g., India’s accommodations in the banking operations and financial investments towards Nonresident Indians and Moldova’s small business driven Program for Attracting Remittances into the Economy "PARE 1 + 1"). The involvement of the “old” diaspora, which would not have to dedicate significant resources to the country of origin, is a critical component of the DRM and MDB frameworks. There is also room for continuation of the “soft” aspect of relations between diasporas and their countries of origin, through education, culture, business, and other kinds of exchanges.

What is left unanswered in this wide range of policy proposals, is the question about diaspora motivation to act beyond individual efforts systemically engaging with the initiatives mentioned above or related alternatives. The scale factor contrasting the country’s common needs and diaspora’s individual contributions is pivotal in maintaining the realistic perspective of the diaspora potential. The next section summarizes some of the results from the Armenian Diaspora Online Survey connecting with some of the points raised in the paper so far.

The Armenian Diaspora Online Survey

The Armenian Diaspora Online Survey (ADOS) ran online from 2015 to the spring of 2018.Footnote1 The ADOS included 28 questions with sub-queries (Appendix A). The survey was publicized on various online community groups via social media, by email, and in various news outlets. By April 2018, the ADOS had collected 513 valid anonymous responses. Methodological challenges notwithstanding, the online survey results could provide new directions for more informed diaspora-home country initiatives (see earlier work on online diaspora survey and research by Oiarzabal, 2012). The diversity of data collected offers additional opportunities for analyzing results with a range of filters (e.g., geographic origin, gender, age, occupation). In addition, the ADOS ended in April 2018, at the time of political upheaval in Armenia, with diaspora’s initial enthusiasm for the changes. A follow-up survey may be foreseeable in the future.

The first group of questions in the ADOS were demographic: 44.4% of the respondents were female and 55.6% male; 99.2% identified as Armenian (82.7% of the respondents said that both their parents were Armenian). The distribution across two age groups was fairly even, with 30% born between 1960 and 1979 and 27% born between 1980 and 1989, whereas while the share for both 1930–1959 and 1990–1999 was 21%.

In terms of their current occupation, 10.3% of the respondents were students, 4.1% were retired, and 69% selected “Other” as their occupation without specifying it here but directly alluding to it in later questions on proposed professional involvement with their home country. In terms of education, 62.2% of the respondents had a college degree, and 15% had a graduate degree, in the social sciences, humanities, and technical fields. These indicators are joint for the “old” and the “new” diaspora cohorts in the survey and on their own merit do not necessarily suggest a dire situation of brain drain from Armenia at present. Instead, as below discussion on engagement with the country suggests, there is an observed trend in the survey responses by which higher educational attainment and professional skills are linked to participants’ stronger inclinations to play a role in the country’s development—contributing to a common good (e.g., Gevorkyan 2016 for some of the preliminary discussions).

The majority of respondents ranked their Armenian language proficiency as high (37.6% said they had native-level proficiency). Eastern Armenian is the official language of the Republic of Armenia, and Western Armenian, selected by 57.3% of respondents, is predominantly spoken in the Armenian diaspora in Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas. Several (but statistically minor group of) respondents contacted us directly by email to say that they considered themselves equally fluent in both Eastern and Western Armenian as native speakers, however, the survey did not permit them to choose both.

Several questions in the survey asked about respondents’ origin, including the country of birth, permanent residence, citizenship, and current residence. The majority of respondents were part of the “old” diaspora, with a wide geographic dispersion in their country of residence. Over 62% of respondents said the country of their current residence was the US, with 7% indicating Canada and 4%, Russia.

A large majority of the respondents had visited Armenia, 73.3% at least once and 42% within a year of taking the survey; 58.7% of the responses indicated no direct immediate family ties in Armenia (the importance of this response will become clear below). These visits were largely short (one to two weeks). This result does not necessarily imply that the trip was for tourism, because business trips are also short.

The respondents indicated that they followed news on Armenia regularly and expressed a strong (49.6%) and somewhat strong (30.6%) emotional attachment to the country (as a historical and cultural homeland) and the broader Armenian community. They were largely interested in Armenian history, politics, culture, economic conditions, and, critically, social development, though at varying degrees. The age groups with the highest degree of local Armenian community involvement were those born in 1930–1979 and 1990–1999.

In general, despite their interest in Armenia’s ongoing socioeconomic development, respondents expressed little interest in moving to Armenia for permanent settlement or for work (implying a contract of short duration). The strongest desire to move to Armenia on a permanent basis was expressed by the youngest age group (20.2% said there was a strong possibility they would do so, the highest of all groups). This result is to be expected, as the prospect of changing one’s domicile necessarily require definite answers about employment and sustained living standards. Both factors can be more easily adjusted at the beginning of a person’s career.

Further, as might be expected in a diaspora study, the majority of the respondents (59.6%) indicated that they had previously donated to an Armenian organization, whereas 82.8% indicated readiness to help organizations (as opposed to individuals) based in Armenia or in the diaspora, though the majority are not currently providing any assistance to anyone in Armenia. On average, the respondents indicated willingness to contribute between $100 and $500 on an annual basis to support such organizations.

This somewhat limited willingness to provide monetary assistance (several answers indicated financial constraints) was significantly offset by the respondents’ emphasis on nonfinancial assistance. The range of possible responses to the survey questions appeared to be insufficient, as many used the comments sections to elaborate on transfers of various kinds of soft skills that they were willing to explore.

Specifically, individual ADOS responses indicated a strong preference for virtual presentations and knowledge sharing as a means of nonfinancial connection with Armenia. Those were followed by stated preferences for volunteering as teachers, research cooperation, infrastructure collaboration, and medical services. These choices largely reflected the respondent’s individual professional background and strongly correlated with education levels. Several respondents with a college or doctoral degree indicated interest in teaching, including some who specified “free of charge” during the summer. Others offered their services in consulting, diplomacy, coaching sports teams (hockey, in particular), and even joining the military reserves. Majority of the educational focus responses came from the college-educated respondents of all ages. On this latter point, it is important to note equally strong interest from both members of the “old” and “new” diaspora, hinting to a positive reverse effect of what earlier might have been termed as a phenomenon of brain drain.

As to the overall respondents’ perception of establishing connection with Armenia, one common thread concerned perceived institutional irregularities in Armenia. These views drove some of the individual responses (visible in raw data), though we are unable to determine the basis for these individual opinions. Another suggests that their active involvement with Armenia was hindered by having insufficient personal funds. At the same time, these respondents also signaled having a strong interest in the social and economic development initiatives in Armenia.

Perhaps most importantly for applied policy were comments about the absence of an organizational engagement infrastructure to support such active involvement and encourage stronger connections between diaspora-based specialists and their counterparties at respective professional entities in Armenia. Potential educators are willing to connect either online or travel to Armenia if an infrastructure existed to engage with local peers, to provide accommodations for longer stays, and to organize volunteering.

The respondents expressed interest not only in humanitarian or charitable assistance but in cooperation in business, education, and other kinds of projects. This could lead diaspora-home country engagement into a new, more sophisticated level of development in the technology age. The diaspora age is also a factor. This is especially significant in Armenia; where the “old” diaspora is mostly made up of the Western Armenian diaspora (identified in the ADOS as those who indicated Western Armenian as their primary language), living in Europe, Middle East, and North America. For these individuals the connection to the present Republic of Armenia is more symbolic, given the nation’s history, than purely “ancestral” in its narrow definition of land of origin. In the ADOS, respondents who are members of Armenia’s new diaspora have higher education levels, though somewhat lower income. These idiosyncratic distinctions appear to be relevant for evaluating the effectiveness of the diaspora-to-homeland engagement models and specific proposals for engagement.

A Proposal for Developing a Diaspora Portal

In the context of a common good proposition guiding this paper, capturing the latent-potential revealed in the ADOS results could be facilitated by developing a diaspora portal (DP) as a web-based sorting and matching database. This DP would be accessible to anyone in the diaspora who has an interest in becoming involved in whichever professional capacity is appropriate by registering online and filling out a form. It would equally be accessible to the residents in the home country. The accuracy of the data and security of exchanges can be ensured with elements of the blockchain technology.

An algorithm then verifies and clears a new request and allocates to an appropriate information bucket and industry category. The latter action results in (1) the information being distributed to the subscribers on the receiving side and (2) automatic storage in the general searchable database. There is a possibility for filtering, sorting, and matching in case of precisely submitted DP signal.

As a new technological solution to an old problem, such a DP could also offer a much-needed formalized institutional framework connecting globally dispersed diaspora professionals with specific development needs in the ancestral homeland. In its ideal setting, a diaspora portal could be a transparent and trustworthy way to overcome the obstacles raised in the ADOS, ensuring a common good outcome and realizing the true diaspora potential.

Self-critique and a Diaspora Model of Development

Whether one approaches the problem of diaspora for home country development from an international business research or economic development perspective, there is a clear need to avoid the simplified predictions of the diasporization trap. The ADOS is an attempt that suggests some initial contours or the possible pragmatic modes of engaging diaspora in sustainable development. The survey, as many, comes with the usual problems from using self-reported data. The anonymous responses raise a valid concern over their accuracy, as well as whether the good intentions expressed will ever be realized. It is equally difficult to confirm the skills and specializations claimed in some of the responses and comments.Footnote2 Here DP may offer a possible objective resolution, as confirmation of an applicant’s claims would be possible with its algorithm and blockchain technology.

Another concern due to relying only on new technology for a solution may be that the gains from cooperation between the diaspora and the home country accrue disproportionately to a particular sector. The problem of niche sector development is clear in the recent concerns raised around IT sector development, especially driven by diaspora efforts (e.g., for India, Pande 2014). In the CEE & FSU the IT sector comprises a minimal share (in terms of revenue and employment) of the overall economy yet the sector benefits from disproportionately large financial gains to its highly skilled labor force. Because it is a niche sector, this pattern raises problems of scalability at the national and international level; lacking broad access to new technology without continuous contacts with foreign counterparts (e.g. diaspora); and evolving regulation. Moreover, the IT sector’s output, though advanced by the diaspora’s participation, may not satisfy domestic economy needs, as consumers opt for more mundane choices, which are needed for the sector’s survival.

Yet, though it is challenging but important to maintain the nonlinear view of the diaspora in development. The individual benefits accruing to a business sector are in many ways analogous to the monetary and social benefits, assuming such, from labor migration. This individuality, to the extent that outward migration and growth in the IT engage diaspora, for the small developing economies raises an urgent need for a wide range appraisal of the diaspora’s role in sustainable development. This is where surveys, such as ADOS, may help inform policymakers and researchers about variety of diaspora modalities maintaining the distinction between individuality and common good. In short, one must know one’s diaspora in devising a sustainable economic development strategy.

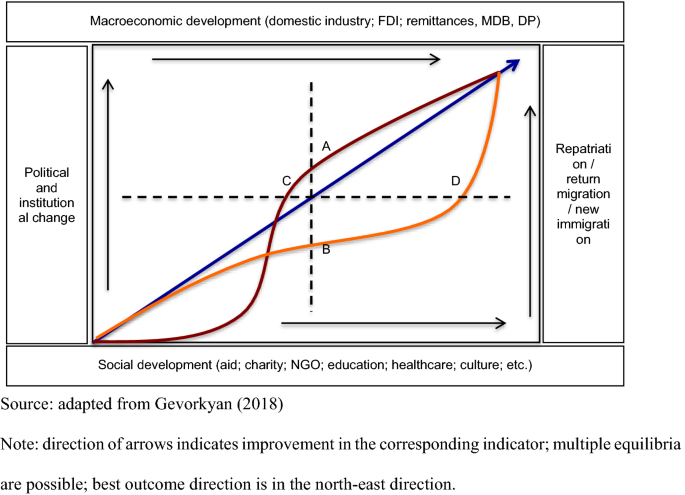

Based on the foregoing discussion, it is possible to sketch a conceptual model of diaspora’s constructive role in development. For that purpose, we adapt from Gevorkyan (2018) and extend here a diaspora driven model of home-country economic development. Without any assumptions on pre-existing engagement instruments, Fig. 3 illustrates the evolution of four critical factors: (1) macroeconomic development, (2) social development, (3) institutional change, and (4) repatriation. The ideal outcome is the positive change in all four factors (e.g., measured as index) and a general movement in the north-east direction of the diagram. The arrows indicate direction of gradual improvement in each category.

Fig. 3

A diaspora driven small country economic development model

The top horizontal axis measures business and economic development. This first factor accounts for including industrial structure, FDI, and remittance flows, accounting for the diaspora’s entrepreneurial contribution to the country’s industrial policy. Note that the MDB and DP play a role in facilitating strong improvement in this factor. The second factor, at the bottom horizontal axis, measures broad socioeconomic development, including a range of “soft” development categories that are often critical in macroeconomic growth. The left-hand vertical axis measures political and institutional change. The right-hand vertical axis measures the gains from migration. This fourth factor accounts for repatriation and return labor migration. However, the migration index should also capture the actual process of immigration, which would be strongly applicable in the cases of the “old” diaspora. Recall, that for this group, the ancestral country may not have been the actual birthplace for neither the “repatriate” nor their parents. In this case, what often is termed as repatriation, diaspora’s return to the ancestral homeland, is more properly defined as immigration. Hence, the immigrant shock of adjustment in a new place may be stronger than in the case of returning temporary labor migrants.

We focus on two scenarios, illustrated by the two curves deviating from the diagonal in Fig. 3, which represents perfectly equal distribution among all four factors. Over time, the deviations occur for many reasons, including the lack of unity across the diaspora (i.e., dispersion) and lack of systemic engagement infrastructure at home. The connection may be sustained by the diaspora’s latent potential as suggested by the ADOS. For example, the points labeled A and B both represent equal improvement in social, business, and economic involvement but vary significantly on the extent of the diaspora’s political involvement in the home country and degree of repatriation (or physical connection). Similarly, points C and D show the same levels of institutional change and repatriation, though with the opposite level of involvement in the economic structure and social development. Scenarios to represent specific countries could be elaborated.

The current scenarios in Fig. 3 encompass concerns that are immediate and challenging to address through economic theorizing—the role of geography, legacy institutions, and predominant economic structures [e.g., see analysis of small open Caribbean economies by Constantine and Khemraj (2019)]. Those are critical to development success in the small CEE/FSU economies. Many of these countries are either landlocked or distanced from global trade routes and face massive geopolitical risks that also shape domestic institutions. As such, it is tempting to view the diaspora as a possible, yet vaguely defined, push factor in national development models.

As far as the potential scenarios, the model in Fig. 3 is anchored by the common good theme of this paper. The four-dimensional view of the model points to some tangible measurements leveraging diaspora’s effectiveness in development. Harnessing this potential also identifies a clear need for a unifying agent in the diaspora-homeland engagement process. Jointly with diaspora portal and similar mechanisms, the central guiding role may be relegated to a dedicated semi-autonomous agency within the formal governmental structure. The agency can be designed to withstand political cycles maintaining operational capacity despite temporary policy changes while remaining focused on key country specific development issues. Overcoming the dispersion effect, leveraging such transparent engagement infrastructure, diasporas then are able to introduce positive systemic change in their home countries’ development process on a wide scale, ranging from social aspects to industrial policy questions. For a small country in a competitive global economy, capitalizing on the diaspora capacity in a common good framework becomes an essential development milestone.

Conclusion

Indeed, the diaspora for development potential has far-reaching and positive promise. Diaspora is seen as an especially critical agent of development following the 2020 pandemic-induced global crisis. Yet, the lack of engagement infrastructure for the diaspora and limited realistic assessments of the said potential stand in sharp contrast to the hypothetical impact based on individual case studies. The problem of diasporization, by which structural voids are hoped to be filled by the diaspora, emerges as central to understanding diaspora’s motivations for home country engagement, as individual gains are contrasted to the common good outcomes.

This paper argues that the modalities of diaspora involvement with the ancestral home and the deterrence factors to that are significantly more complex and diverse than previously assumed. The lessons from the survey presented in this paper may be relevant across small economies in emphasizing the heterogeneity of the dispersion with consequences for macroeconomic and social development. From the diaspora’s perspective, the connection with the home country is often a function of the generational distance and complexity of the socio-economic interactions. From the home country’s perspective, the connection with its diaspora requires consistency and appreciation of diaspora’s significance in a more systemic development view.

The model derived in this analysis offers some measurable aspects of diaspora’s broader role in economic development. The institutional instruments discussed in the paper and those that are yet to emerge enter into the model as key components revealing diaspora’s true potential in the home economy converting isolated trends in a more systemic and impactful collective effort. Still, conceptual and empirical representations notwithstanding, at a more philosophical level, it is out of a difficult balance of diverse circumstances that the two communities—the home country and its diaspora—may build effective engagement infrastructure connecting with each other.

Original article.

Original article.

-

Repat Story

-webp(85)-o(png).webp?token=951ee8abc4b68742636fcca4cd7454a3) 23.10.2025Teaching, Healing, and Inspiring through Music: Kamil Tchalaev’s “Wild School”

23.10.2025Teaching, Healing, and Inspiring through Music: Kamil Tchalaev’s “Wild School” -

Repat Story

-webp(85)-o(png).webp?token=cca66f7395cce000bfb85adf04f02cdc) 17.10.2025Children’s Dreams — Motivation to Work: The Founding of the Alaverdi Boxing School

17.10.2025Children’s Dreams — Motivation to Work: The Founding of the Alaverdi Boxing School

-webp(85)-o(png).webp?token=64584fca19b0f684f36ab0f30125b083)

-webp(85)-o(png).webp?token=8c62dd428eedd66aa47f9c10d53f2a16)